The truth is however, that D.C. policy-makers on both sides of the aisle stifle jobs and opportunity with regulations and policies that hurt our work force; and often, it flies in the face of common sense. The perfect example of this is the debate over industrial hemp.

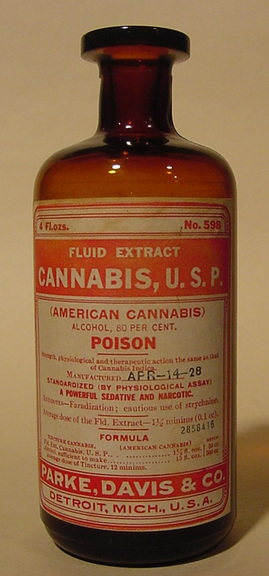

Prior to World War II, Kentucky led the nation in providing 94 percent of all industrialized hemp. However, it became outlawed under an umbrella law that made marijuana illegal. This was simply because they are in the same botanical family and look similar.

However, there are major differences in the two plants. Cannabis consists of a significantly higher percentage of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), a mind-altering chemical, while industrial hemp plants contain less than 0.3 percent.

Comparing hemp to marijuana is like comparing poppy seeds found on bagels to OxyContin. Poppy seeds are in the same family of opiate; the same family that contains codeine, morphine, OxyContin and even heroin.

Yet, you can buy and consume food containing poppy seeds, as thousands of Americans do each day, without experiencing the narcotic effects the rest of its plant is harvested for.

Therefore, the issue with hemp is not that the plant is harmful. It's that the plant might be mistaken for cannabis.

This presents some challenges for law enforcement. Nevertheless, we can address those challenges. In addition, we can return to growing and producing hemp in Kentucky as well as other parts of America, and in the process, create jobs and opportunity in the USA.

Let me share an example of the economic potential for industrial hemp.

Dr. Bronner's Magic Soaps is based in California and sells products made from hemp plants. David Bronner, the company's CEO, says it grossed over $50 million in sales this past year. However, since the production of industrial hemp is outlawed in America, the company must import 100 percent of the hemp used in their products from other countries.

The company sends hundreds of thousands of U.S. dollars every year to other countries because American farmers are not allowed to grow this plant. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation in the world that does not allow the legal farming of hemp.

Today, hemp products are sold around the U.S. in forms of paper, cosmetics, lotions, auto parts, clothes, cattle feed, and so much more. If we were to start using hemp plants again for paper, we could ultimately replace using trees as the main source for our paper supply.

One acre of industrial hemp plants can grow around 15,000 pounds of green hemp in about 110 days. For every ton of hemp converted into paper, we could save 12 trees. It is a renewable, sustainable, environmentally conscious crop.

Back in August, Kentucky Agriculture Commissioner James Comer and a bipartisan group of legislators promised Kentuckians that they would join the fight to allow the growth and production of industrial hemp. Comer stated that day that the soil and the climate in Kentucky are perfect for the growth of hemp, and that could ultimately allow the commonwealth to be the nation's top producer.

Recently, Comer revived the long-dormant Kentucky Hemp Commission by calling its first meeting in more than 10 years. This took real leadership and I applaud him for his action. To help get the ball rolling, Dr. Bronner wrote a $50,000 check to the commission.

My vision for the farmers and manufacturers of Kentucky and other parts of America is to see us start growing hemp, creating jobs, and leading the nation in this industry again. These jobs will be ripe for the taking, but we must act now.